France around 1830 was rich in factions and tendencies, and you can’t read about the French literature of the first half of the 19th century without running into a large number of competing groups — political, literary, or simply social. So I have compiled a list.

France changed its form of government four times between 1787 and 1830 (plus another couple of changes during the revolutionary period), and in 1830 partisans of most of the past regimes were still around. The main political factions were the ultra-royalists, the Girondin republicans, the Jacobin republicans, the American-style republicans, the Bonapartists, and the moderate semi-liberal royalists who took power with the July Revolution. Besides these there were utopian socialist followers of Fourier or Saint-Simon, but while they got their ideas out, they didn’t really have a political role, and whatever groups the bottom 70% of the population had were regarded with fear and disdain.

The only faction that was probably lacking was one supporting the overthrown Restoration government. The Bourbons had been imposed on France by England and Germany after Napoleon’s defeat, and while they weren’t royalist enough for the ultras, they were too royalist for everyone else. This set a pattern for France — the moderate royalist regime established in 1830 didn’t make anyone happy either, and examples could be multiplied.

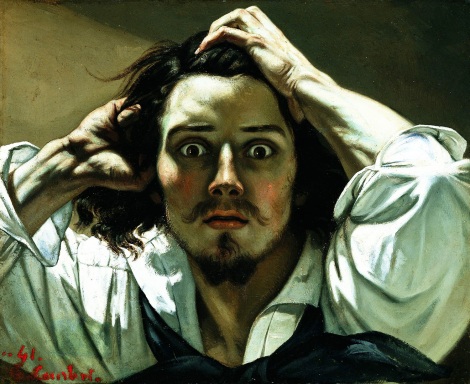

In the literary world, the big split was between the romantics just coming onstage, and everyone else: the classicists, philosophes, and republicans. To begin with, the romantics were led by Charles Nodier of l’Arsenal (a library), but around 1830 Victor Hugo seized power for his Cénacle, and a little after 1830 Théophile Gautier and Petrus Borel established the Petit Cénacle, which included younger writers. (Nodier, Hugo, and Gautier became famous for praising the writing of anyone who ever brought them a manuscript.) The first two groups were just salons, but many of the members of the Petit Cénacle were housemates, and they threw rowdy parties of a type which should be familiar to many readers.

Most of the factional activity took place among the romantics. The romantic factions were Les Meditateurs, Les Frénétiques, Les Larmoyants, Les Illuminés, Le Petit Cénacle, Les Jeunes-France, Les Buveurs d’Eau, the literary Bousingots, the political Bousingots, Les Badouillards, Les Muscardins (dormice), Les Dandys and Les Bohème.* (more…)